L-1 Lagrange Point

Near Enlil I-a

Enlil System

Captain’s Log, July 2nd 2330. Intrepid has successfully completed its grav jump to Enlil, emerging near the moon Enlil I-a. According to credible reports received by Constellation, this moon contains previously-uncharted Vytinium deposits. Our primary mission is to conduct a survey of this inhospitable moon and determine if it contains deposits in sufficient density for commercial exploitation.

We exited our grav jump inside a fairly dense Lagrangian debris field. While I didn’t expect to find anything too exotic out this way, we did take some time to shatter one of the rocks and analyze it’s contents. We didn’t find anything more useful than iron ore, and while it’s useful to be aware of a reliable source of iron, it didn’t warrant any further action from us at the time.

While Lin supervised the asteroid fracturing, Cora conducted long-range scans of the other bodies in the system. She came back with a few results that might warrant more addition in the future. Enlil II has a temperate climate and a strong magnetosphere, though it’s methane-based atmosphere doesn’t make it ideal for colonization. It does have significant biomarkers however, along with a few anomalous readings. The frozen moon Enlil VI-a also stood out for its unusually large neon deposits, as did the somewhat wide distribution of tantalum deposits throughout the system.

But our interest today was on Enlil I-a. The furiously hot moon – median temperature 251 degrees Celsius – nevertheless had an oxygen concentration of 18% and indications of surface life forms. Granted, we’d just finished observing an environment that rained liquid oxygen and still managed to support life, but extremophiles of any sort are always impressive. Enlil I-a did have a reasonably strong magnetosphere, but out of an abundance of caution I restricted shore excursions to night hours; I hoped that would grant at least some relief from the extreme heat.

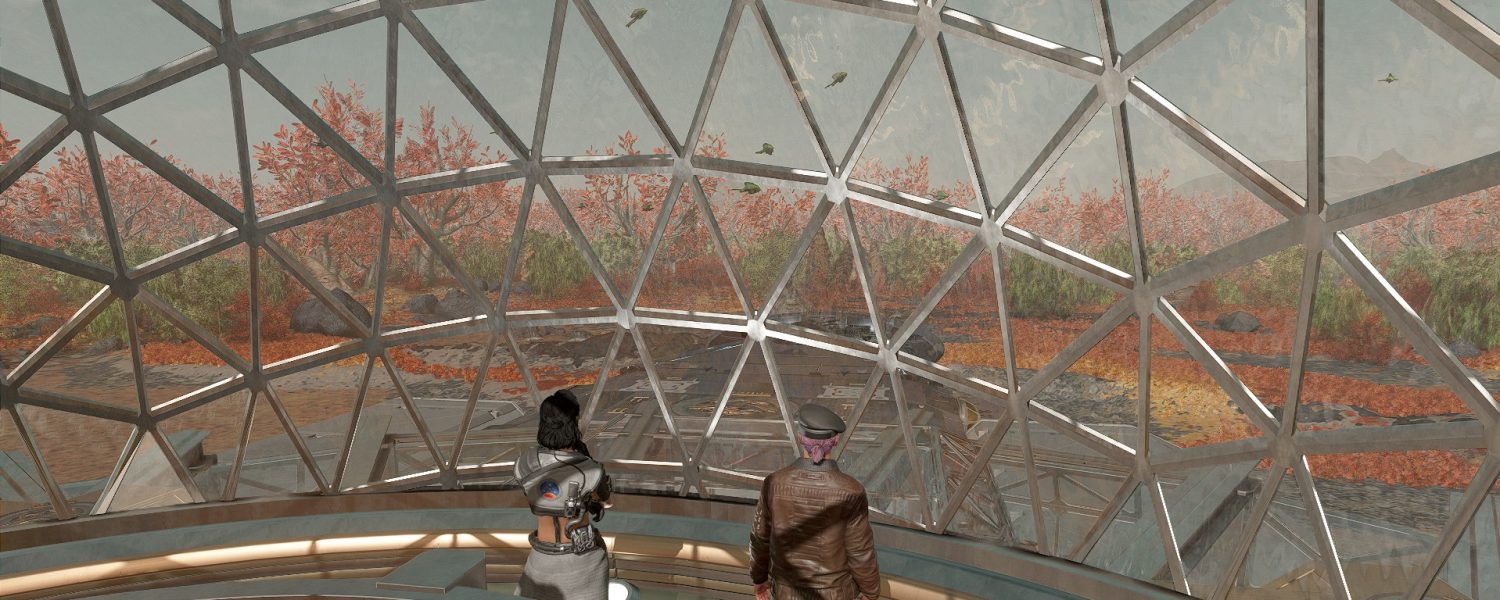

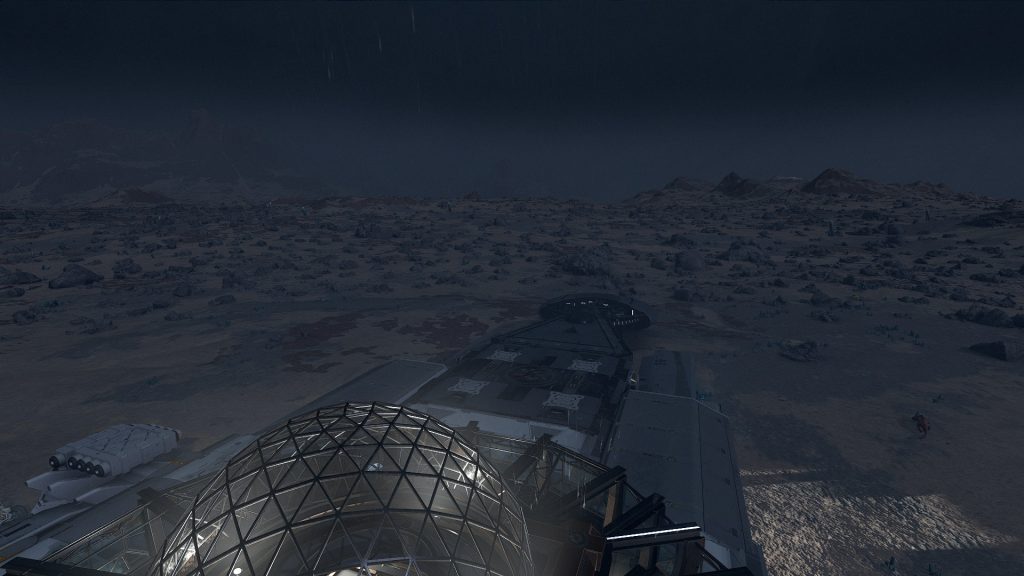

Sam had managed to land only a few hundred meters from the reported Vytinium cave, but I wasn’t confident our suits would be sufficient to conduct extended mining operations in the heat. Consequently, my first goal was to construct a climate controlled habitat adjoining the cave, so Lin and Heller could take downtime as needed without having to return all the way to Intrepid.

While we waited for sunset, I surveyed the terrain from the command module. The desert landscape was broken up by dense clusters of radioactive autunite crystals. We’d need to give them reasonably wide berth… but I have to admit, I wish there was a lunar eclipse coming up soon… the reflected UV light from the planet would cause a truly spectacular display of fluorescence on the moon’s night side.

But the environmental radiation hazard just underscored the need for a safe habitat at the dig site. I worked out a plan with Lin that should cover our minimum safety requirements… it wouldn’t be much, just a simple shielded habitation module and an airlock, but it would be enough to give them a place to rest and recharge their suits’ cooling systems.

I also observed with great interest the complex life forms that shared the desert with us. Squad creatures with leathery hides and long aardvark-like snouts, Doctor Tannehill suspected they hunted by rooting out burrowing creatures – and then burrowed in themselves when they needed to escape from the heat. I made a mental note to try and get scans of them if we could do so safely.

Perhaps one factor working in our advantage on the moon was its 72 hour day. It was 4500 hours when we touched down, and Sarah calculated sunset as no later than 6000 hours. That gave us two shifts to figure out our plan for setting up the shielded habitat, and then three shifts of uninterrupted night to get it build and maybe even start the exploration of the cave.

Once the sun receded behind the horizon, I watched Lin and Heller take off in the rover. I felt some envy for them, but I also felt apprehension. Those two were seasoned pros at the mining business, but this was an environment with no toleration for mistakes.

So when they returned a few hours later, I was expecting a briefing on the plan for setting up the hab module. Instead, I got a whole parade of unexpected and/or unwanted pieces of information. First, some good news: the interior of the cave system was substantially cooler than the surface. If Lin had been going to make this a protracted expedition, they could just set up a base camp inside the cave.

Oh, yes, if they were going to. That’s where the bad news came in. There was barely any Vytinium there. She and Heller recovered about 5 kilograms in total, with no signs of any veins or other deeper deposits. And the area around he cave was a bust, too. They had a single unusual reading on their scanners that might lead to a hail-mary discovery, but things didn’t look promising.

Also, Heller had to get elbow deep in a truly enormous pile of animal waste to recover one of the chunks of ore. The cave was full of dead animals, Lin noted as an afterthought. Apparently some had gotten lost in the cave and died of hypothermia before they could return to their preferred inferno.

I agreed with Lin that we should check out the distant sensor contact, and I wanted to get my own eyes on some of the wildlife here, so I volunteered to drive. The contact was half a kilometer west of the landing zone, and photography we’d taken on the way down suggested it was situated in a particularly dense concentration of the radioactive crystals. Before we set off, Cora briefly tried to convince me to bring her along – for educational purposes, of course – but I had to turn her down. She had definitely not earned her Environmental Conditioning badge and so soon after my heart-to-heart with Sarah about her training program I was not going to make an exception.

Just as we arrived at the anomaly, Moara’s voice broke in over the comm. “Keep it quick, you too. Your old nemesis the water cycle is on the way, and it’s not so much water as it’s glycerol… clouds are reading 275 degrees on the thermals. I do not recommend staying out in the rain.”

“Copy that, but… this is pretty impressive.”

It was a veritable forest of crystals. Not just the uranium ones but red erythrite and vivid blue cobalt quartz. I really wanted to spend some time here appreciating the visual spectacle, but with the bad weather coming in we retreated for the moment. I decided at that moment that I’d risk the daytime heat just to see this under full light before we departed.

But while I settled in to wait for sunrise – still many hours away – I decided to give Sarah the bad news.

“The mission’s a bust, isn’t it?” she asked as I approached.

“Was I that obvious?”

“Heller filled me in about the cave. I can’t believe we traveled 75 light years to collect five kilograms of rock. That’s,” she laughed ruefully, “that’s really playing up to the stereotype that we’re a bunch of spoiled rich kids wasting their familys’ money.”

“Mostly just wasting Walter Stroud’s money,” I suggested, before amending, “but I wouldn’t call it a bust. We made some very interesting discoveries, including some survey data with potential for commercialization.”

Snorting she challenged me, “you mean the drug planet? Oh, Walter will love that. Though perhaps Benjamin Bayu would be receptive to the information.”

“I was thinking more about the gas bags boogers we could turn into heart disease medicine, but now that you mention Bayu…”

“No! God, forget I ever said that.”

“Fair enough, consider it forgotten. We’ll also be coming home to a pretty generous honorarium when we turn over that massive haul of contraband to the TMD, and Cora did say she detected biomarkers on that planet in the temperate zone. I certainly don’t object to spending some more time exploring before we head back.”

Waiting out the storm was a tedious process, but at least we got a good light show. The lightning that accompanies the scalding rain was bold and intense, connecting with the crystal pillars in blinding flashes. I’ve always found thunderstorms to be paradoxically calming, and when I went off shift I found I slept easily against the background rumble of thunder.

We took advantage of the long night to do a full diagnostic workup on the ship. All things considered, she’d held up well so far on the voyage, but Jazz identified one or two pieces of preventive maintenance to square away, so we’d be in top shape when we left. I also talked some more with the rest of the team and found there was broad interest in a visit to Enlil II. At a minimum, it would give us additional survey data and an opportunity for a proper shore excursion, and if we were lucky we might find something to offset the failure of the Vytinium prospect.

The crystaline forest was truly something to behold under daylight. Words can’t really do it justice. Lin and I collected samples of the different crystaline species, careful to do as little damage as possible, and while I had my doubts that the data would command much value, the process of obtaining it was reward enough.

As we returned to the ship, we witnessed a variety of different creatures emerging from holes and dugouts to greet the rising sun. Taking a more leisurely route back to Intrepid, we bolstered our biological data, enough that I’m confident our survey report will fully meet Vladimir’s standards. Our orbital scans suggested that the other biomes vary only in degree rather than kind, so our data should be broadly representative of the entire moon. We’ll shortly set course for Enlil II, which should make for a more involved survey operation – and hopefully offer us some valuable surprises.

End log.

July 4th, 2330

Days Elapsed: 12

Fuel Consumption: 68.26 kg

Fuel Acquired: 0

Fuel Remaining: 171.92 kg

Injuries Acquired: 0

Lifetime Injuries: 4

Behind the Scenes

I’ve played 360 hours of Starfield, and this is my first progress-blocking bug. Does something look odd to you about this Vytinium deposit? Perhaps the fact that is spawned in a debug room instead of in the cave! Fortunately, I had the wherewithall to trace the reference but in order to solve this quest I had to rely on the debug console… which I shouldn’t have to.