Captain’s Log, July 4th, 2330. Having completed our survey of Enlil I-a, Intrepid is proceeding to Enlil II, where we will document the planet’s ecosystem and geology. Thanks to the significantly shorter distances between planets compared to Delta Vulpes, we expect to arrive in a matter of a few hours.

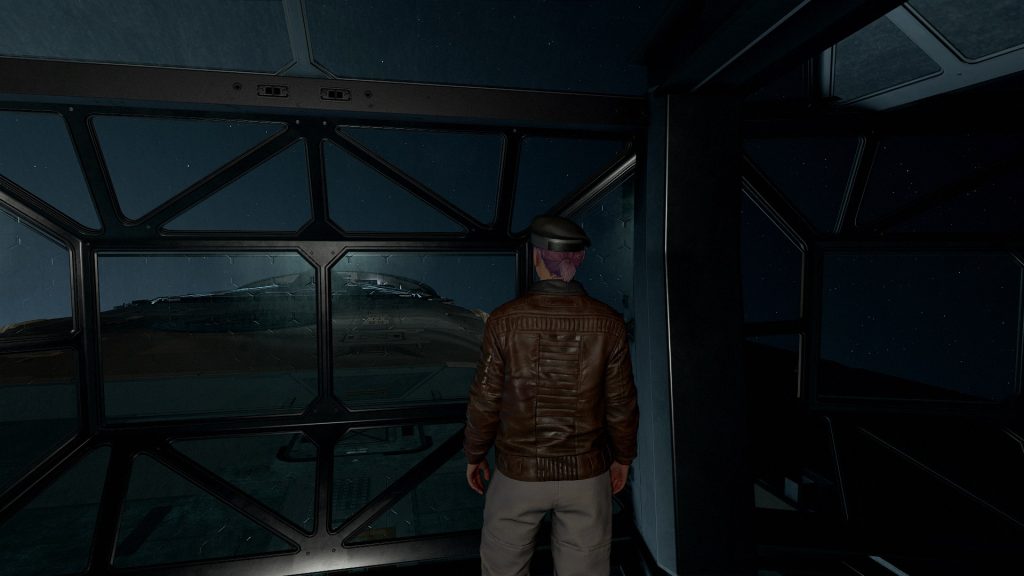

It’s hard to visualize speed in deep space. Grav jumps, of course, are almost instantaneous and the visual distortions caused by the gravity field create an effect that the mind translates into rapid motion. But transit under conventional thrust, even boosted by the grav field… once nearby planets fade away, it almost feels like you’re standing still.

But there’s also something calm about the endless stretch of space. Just me and my crew, and the stars. I know some people say they feel an intense sense of dread when they’re in deep space, but for me it’s relaxing. Like I’ve stepped away from the troubles and complications of the world. That’s one thing, a bit perversely I suppose, that I’m concerned about with Dauntless.

Sarah and Walter have all sorts of plans for the ship, and one is to have a have a large living space area with a park and a swimming pool. I understand why they want these things, but I’m worried they’ll bring too much of ‘home’ with us into space. They’ll be no escape from normalcy, and I feel like we’ll be losing something in the process.

Since our excursion to Enlil II is going to have a strong focus on biology, Doctor Tannehill will be first on the ground with me when we land. We’ll be in pressure suits on account of the methane atmosphere, but I still needed to talk to her about her away party dress for future missions.

I’d promised to provide her with some suitable gear for potentially hostile environments, but I hadn’t brought much on this voyage myself – just a few changes of clothes and my set of body armor (which I surely need at some point in the future). But I had brought a couple mementos from past adventures, including an outfit I’d bought on the Key during my undercover work for UC SYSDEF.

Tannehill did not seem impressed with it.

“This looks awful,” she complained, plucking at the different fittings and accessories, “and it ruins all the lines of my figure. I might as well just wear a trash bag.”

“I can arrange for that next time we visit Neon, if you want. Plenty of folks would be happy to trade their humble getups for your fancy party clothes.”

“You wouldn’t dare…” she hissed, but I took control of the conversation before she got too spun up.

“Look, the goal isn’t to make you look pretty. Hungry animals won’t care, and to the extent that pirates or spacers might care, it won’t work to your advantage. The goal here is safety and utility.” I poked a finger at the strap just below the neck. “Look, it’s even got a D-ring. I thought you liked D-rings.”

Tannehill groaned with an exasperation that only a 20-something can muster, reminding me that no matter how talented a doctor she was, she still had a lot of practical experience to acquire. I walked her through the rest of the features of the utility suit before I (‘finally’) let her change into something more comfortable, but by the end she’d at least acknowledged that the suit would do a better job keeping her safe than her strappy dance thing.

Enlil II certainly looked the part of a planet friendly to life. Big blue oceans, complex cloud patterns, varied biomes and climate zones. This would be a nice change of pace from our last few excursions. With a very strong magnetosphere, solar radiation shouldn’t post much of a threat, and likewise we shouldn’t encounter any hazardous temperature swings in its generally temperate climate. Our orbital scans did reveal that the planet’s water supply had unsafe levels of heavy metals, which probably also translated into the whole food chain being unsafe for human consumption without a lot of processing, but we weren’t planning on having a hunting safari.

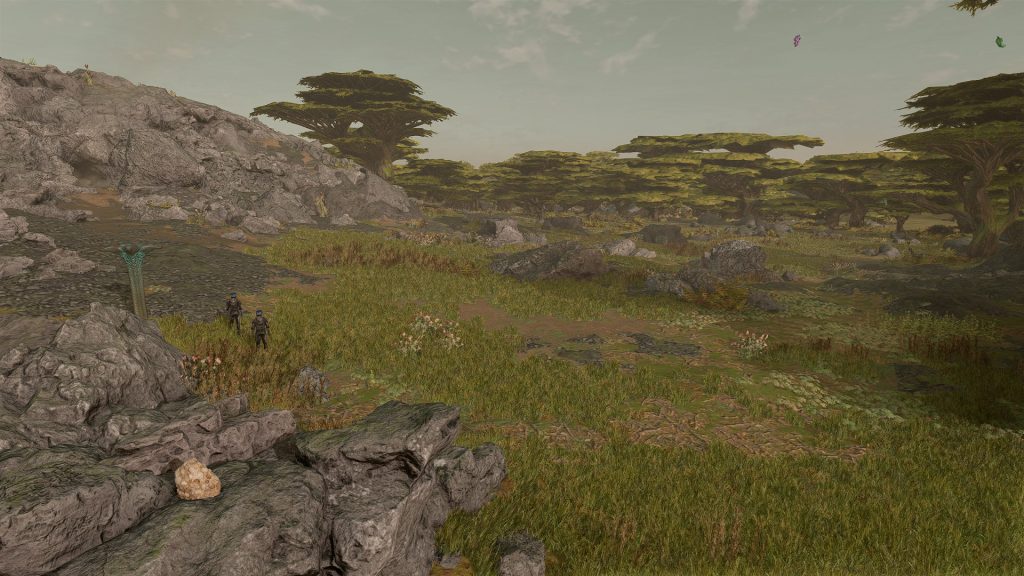

We made our first landing in a coastal savannah zone close to the equator. Airborne filter-feeders and long-necked, galloping land animals dispelled any concern that the biomarkers might have been a false positive. Plenty of life forms here to examine, along with complex plant life that we’d also want to learn more about.

Somewhat reprising our approach to surveying Jaffa II, Tannehill and I started with a walk around the landing zone. This is standard practice to get a feel for the immediate surroundings and also to identify any anomalies on long-range scanners for later visits.

If anything, the initial view from the ship sold this planet short. As soon as the turbulence of our landing subsided, the sky filled practically to capacity with the filter feeders, and below them all manner of low-gravity adapted animals grazed on the extensive plant life. Tannehill was hard at work with her scanner, already pointing out a few more distant points that we might want to examine after we’d finished walking the perimeter.

One thing that I found interesting, even if it wasn’t especially uncommon, was the presence of cagebrains. These creatures, characterized by a porous, bony lattice encasing their central nervous system, are one of those odd little mysteries of the Settled Systems. They’ve evolved seemingly independently on dozens of worlds, much like the way crabs evolved on Old Earth, but no one really has a good theory for ‘why.’ Obviously there’s something adaptive about that sort of body structure, but the scientists seem to be a long way from working it out.

Plenty of interesting plant life on the savannah as well. Of course there were conventional trees – another one of those life forms that tends to evolve almost everywhere, but some of the local variations had interesting properties. Notably, one tree species was bedecked with heavy fruit. We ran a field test on some samples and found them to be rich in berberine, a metabolic agent with anti-inflammatory applications.

After a few hours, the air quality started to drop considerably. While our pressure suits shielded us from direct exposure, the wind-blown sand and particulates weren’t good for our suit seals and ECUs, and we made our way back inside Intrepid to wait it out. Tannehill told me that our outing had been very successful however; she’d got very high quality scans on multiple examples of five different animal species and brought back samples of three different plants with noteworthy characteristics.

My geological scan hadn’t been quite as fruitful – while I’d found small surface deposits of many of the minerals our orbital scans had detected, the immediate vicinity of the landing zone did not reveal any large deposits suitable for mining. I’d mentioned earlier that this was one of several planets in the Enlil system with deposits of tantalum ore, which has widespread commercial applications in laser technology and gas extraction systems. While I don’t plan to establish a mining facility this far out for anything less than a true exotic like Vytinium, if we can document the location of major tantalum veins it’ll greatly increase the value of our survey data.

The cagebrains – both their mature, mobile forms and their larval forms that more resembled plants – intrigued me with heir reaction to the dust storm. Or rather, their lack of reaction. I would have assumed they’d have had some kind of defense mechanism to shield their delicate brains against the windborne grit, but instead they seemed unbothered. Perhaps their neural cores were just tougher than I’d assumed, or perhaps their exposure to the blowing dust actually served some adaptive purpose. I suspected it would remain a mystery without significantly more study.

While the storm raged on, Tannehill and I worked out a plan for what to do the following day. We detected some unusual life signs during our perimeter walk some distance to the west, and that would be our first stop. From there, we’d head southwest and investigate a large oasis that Sam observed during landing procedures. Finally, we’d push all the way east to the coastline and obtain water samples – we’d also scan for any large aquatic life forms while we were there.

It would make for a full day of work, but I was pretty confident we could visit all these points of interest before nightfall. Unless we ran into further points of interest that called for a longer stay, we’d then make a suborbital flight to one of the other biomes to continue our survey.

I liked this plan, but I wasn’t going to be the one carrying it out. Cora was overdue for some field experience – indeed, she couldn’t complete some of her key certifications in the training program if she didn’t get some – and I was confident that there weren’t any major threats in this biome that Tannehill couldn’t run away from if she needed to. The closest we saw to any aggression from the local wildlife had been when I used the laser cutter to take some rock samples – that had been greeted with a chorus of very disapproving roars from the braincages – but those two wouldn’t be doing any mining work this time.

So I got to stay behind on the observation deck while the two of them zoomed off in search of the unknown. There was a part of me who wanted to hold the two of them back on the grounds that neither was experienced enough to lead the other, but I forced myself to squelch the impulse. Those two were never going to achieve their full potential if I helicopter parented them into mediocrity.

Though based on their report, perhaps I didn’t helicopter parent them quite enough – almost as soon as they left the garage, those two went off the mission plan and made a bee line for the coast. Credit where credit’s due, they documented a (hideously poisonous) species of trilobite beachcomber that lived on the edge of the (hideously poisonous) ocean, bringing back tissue samples of the trilobites and water samples of the ocean.

In addition to the heavy metal salts we’d detected from orbit, the ocean water was thoroughly blended with silicic acid, rendering it quite corrosive. The trilobites, meanwhile, had significant amounts of D4 siloxane in their tissue, probably explaining why nothing seemed to be eating them. Between the silicic acid and the siloxane, Sam raised the theory that undersea chlorosilane vents may be playing a role in the toxicity of the seawater, and I’m inclined to agree.

From there, they proceeded to push almost a kilometer south going after another anomalous lifesign on long range scanners. It was located at a small cluster of ponds very similar to their actual target, which leads me to believe this ended up getting them the same or at least similar results that they would have had if they’d stayed on mission, but still… I was not entirely impressed.

What they found was indeed interesting. I’d wondered if the gnarled, carbonaceous mounds we’d seen closer to the ship were signs of builder microbes, and the larger examples that Cora and Tannehill found confirmed it. Enlil II was far from the first planet where surveyors had found eusocial, highly organized colony organisms like this, but it was always an interesting discovery when they turned up. Old Earth had ants and termites, but in the wider galaxy that niche seems to be almost exclusively filled by microbial life, growing into huge colonies whose specialized members acted analogously to the cells of a more conventional organism.

There’s some debate within MAST about just how sentient these colony organisms are and whether or not some degree of communication might be possible. The “smart microbes” camp has been advocating for giving them special protected status for some time, but the proposals are all deadlocked at the cabinet level and they remain in a legal limbo from a conservation point of view. Constellation’s policy, however, is to keep hands off, and so I was happy at least that Cora and Tannehill didn’t damage the structures or try to extract any samples.

They never actually made it to the oasis, and with more bad weather coming in I decided to cut my losses and tell Sam to head for the next landing zone. Meanwhile, I had a discussion with both Cora and Doctor Tannehill about the importance of sticking to planned mission profiles.

To give credit where credit’s due, neither of them tried to throw the other under the bus. They accepted responsibility for going off the mission and gave a cogent explanation for their reasoning that didn’t quite break into excuse territory. I, in turn, explained to them the risks of deviating from the plan and walked them through our protocol for making changes to a mission plan.

Meanwhile, Sam had deposited us to a mist-shrouded mountain valley in the planet’s southern hemisphere. Heller and Barrett did the perimeter sweep and came back not just with data on another new plant species but several readings that pointed to additional areas of interest. Working from that initial survey, Sarah and I took the rover out towards the more distant readings.

On the way to our first contact, Sarah pointed out some odd rock formations on the mountainside. Closer examination revealed them to be chlorosilane seeps – one of the only remaining chemical features we hadn’t verified on the ground yet – and we stopped to collect samples.

When we finally reached the anomalous scanner return, we found ourselves at what I think is best described as a watering hole. The hilltop pond was inhabited by most of the species we’d identified in the mountain biome, as well as a few of the sedentary juvenile braincages. We also observed large deposits of animal bones both in the water and around the shore.

The water itself was positively bubbling with hydrogen chloride gas, so we didn’t try to reach the small island at the center, but we did recover an egg or chrysalis from a shoreside nest – something I was very interested in taking a look at back on Intrepid.

The other area we visited was a rocky outcropping that Barrett had correctly identified as containing a cave entrance. Even before we got inside we observed some skeletal remains mixed in with the rock litter, and I had a hunch that we’d be finding significantly more once we were inside.

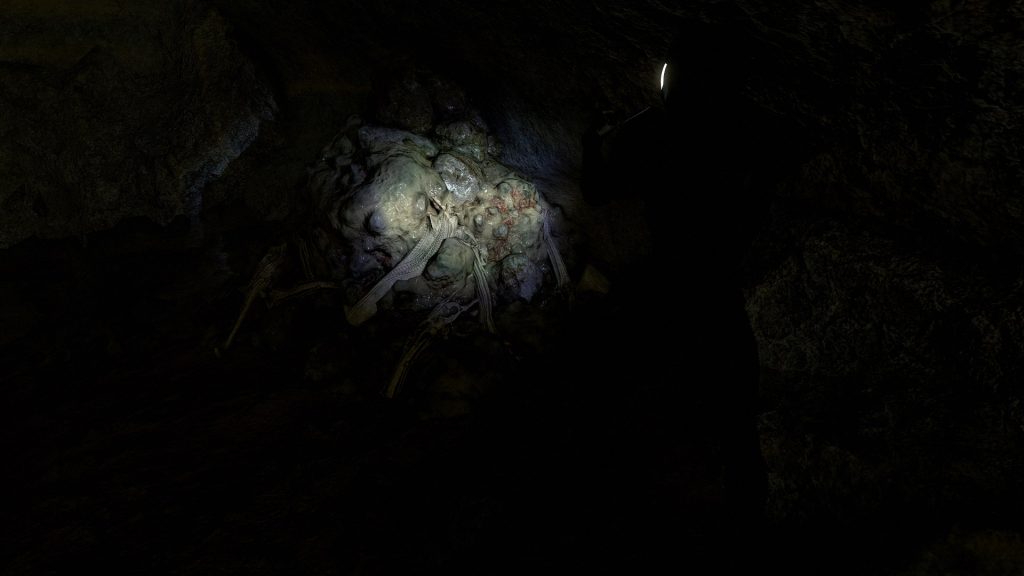

While that wasn’t entirely a false assumption, the cave wasn’t so much a graveyard as it was a larder. This particular cave dove down fairly straight and deep along a sharp incline until it reached a small cavern that some animal was obviously living in. Fortunately, they weren’t home, but we did find a number of carcasses of an animal we’d nicknamed the Crabfly.

We knew from our earlier observation that the crabflies appeared to be herbivores, and that their salivary fluids – found left behind on plants they were eating – had a complex mix of solvents and enzymes, as well as 4-ketoisophorone, one of the main aromatics associated with saffron spice. I took a moment to dissect one of the carcasses and make a more detailed study of its anatomy, and I made two interesting discoveries.

First, it appeared that the crabfly reproduced by burying a seed pod which would later protect and gestate the offspring. Second, just underneath the seed’s rigid outer shell, it contained a thick insulating layer that was chemically very similar to the silicone-based sealants used in spacecraft repair. Considering the mild climate on Enlil II, I wondered if the crabflies would be viable for farming. The answer to that would depend a lot on their temperament and a much better understanding of their life cycle, but I made a mental note to include the information in our survey report.

On the way back to Intrepid, my scanners picked up another probably cave some distance to the north. I consulted with Moara on the commlink, and after confirming that the weather pattern looked clear we agreed to add a stop there to the return trip. I’m glad we did, because we found quite a treat down there.

This cave intersected a subterranean builder-microbe colony; since reputable scientists don’t disturb the builder mounds, data on their underground components is extremely rare. While we didn’t lay a finger on the actual structures, we were able to take extensive readings with our scanners, including gathering data on VOCs and pheromones emitting from the pores in the colony.

Equally interestingly, we observed several areas where the colony structures seemed to have concentrated around deposits of lepidolite and pools of liquid caesium. Radioactive and rare on Enlil II (at least on the surface), I wondered what role the caesium pools played in the function of these eusocial microbes. I collected as much data as I could without disrupting the colony, then Sarah and I returned to the rover.

We actually spotted both a third cave and also a meteorite crater on the return trip, but Moara advised me that a thunderstorm was inbound, and while he didn’t believe it posed an environmental hazard I was a little concerned about the potential for flash flooding in the steep mountain terrain. Consequently, we returned back to Intrepid to review our findings and consider our next steps.

The team greeted our findings with great interest, and we seriously considered staying in the mountains for another day to explore the third cave, but at length we decided to instead make a final suborbital flight to the equatorial forest region northwest of our current landing zone. This would almost certainly offer us more species to inspect, and Lin reminded us that we had now spent enough time in Enlil that our fuel reserves back in Delta Vulpes should be ready for the return trip. While we had the supplies for a few more weeks at least, Jasmine was concerned about the condition of the main water purifier and she recommend that we play it safe with expediting the rest of the mission.

On arrival, our perimeter sweep revealed that we had landed in a dense concentration of builder-microbe colonies. We’d actually have to exercise considerable care to avoid interacting with them. We also identified a number of new plant species, a nearby cave, and an unusual rock formation. While we’d have to tread carefully in this area, bursting with life as it was, I was confident that this final landing zone would offer more valuable insights into life on Enlil II.

We spent the rest of that day planning our route to the target areas as well as helping Jasmine with a teardown on the water purifier. The good news is that it didn’t look like it was facing an imminent failure, but it had clearly picked up a lot more wear and tear than Intrepid‘s specs said it should have by now. I decided that when we got back to the Settled Systems, I’d have the whole system swapped out for new – and recommend that we plan for a 10% increase in capacity for Dauntless to account for unplanned stress on the system.

The next morning, Barrett and I piled into the rover and we started heading for the cave. As we picked our way through the dense terrain, I started to wonder if we would have been better off just going on foot – but I knew that was just frustration talking. If push came to shove, we could kick in the thrusters on the rover and cover a lot of ground very fast, even if it would cause collateral damage to the plant life I’d prefer to avoid. That meant that in an emergency, the rover might be the difference between us getting back to the ship and… us not. So I gritted my teeth and just settled in for a slow and bumpy ride through the forest.

The cave itself was located in a pretty little meadow clearing north of our landing zone, densely packed with plant life and generally looking pretty hospitable. Of course, that was all an illusion – we’d only identified one plant species on the planet that was even compatible with human metabolism, and most of the life forms here were extremely poisonous.

The cave itself quickly opened into a broad and relatively low-ceilinged cavern, containing more than a few crabfly carcasses, including a nasty decomposing pile of them towards the back. In all the biomes we visited we’d piles of dead crabflies here and there, and at the time we’d assumed this was just the result of predation; however, Barrett floated a different theory as we walked this cave.

“What if the fly dying is actually part of their life cycle?” he suggested. “Maybe when they’re ready to lay their eggs, they just drop dead and as the carcass decomposes the seeds work their way down into the ground.”

“That’s pretty grizzly,” I said, “but hardly unheard of. Let’s get some scans of the biomass mound in the back, maybe it’ll offer some insight into your theory.”

That pile of semi-liquid biomass yielded some interesting results. In particular, the aromatic solvents we’d detected in earlier samples of crabfly tissue were very prevalent – in excess of what I’d have expected from simple decomposition. And the seed pods within seemed fully intact, protected by their silocone-based protective shell.

“You know, Barrett, I think you might be on to something,” I said as I showed him the results from my scanner.

“Uh, huh, would you look at that? I think we’ve got another paragraph or two to add to the survey report.”

“Well, you’ll get the credit for it. I wouldn’t have thought of that wrinkle, and it explains a lot of what we saw at the other landing zones.”

We walked through the rest of the cavern, hopping and skipping a bit to avoid some slushy pools that were far too dense with uranium salts to just casually wade through. In the process, we pulled down a few mineral samples from the walls, but after maybe another hour we were confident we’d found everything this location had to offer.

“Shall we go observe some scene rocks?” Barrett suggested.

The route to the rock formation took us through dense thickets of juvenile cagebrains and then a swampy wetland area positively bubbling with corrosive vapor. We managed to get through it by laying on the speed with the rover, but the experience reinforced my feeling that I’d made the right decision not just hiking to our targets. Getting around that swampy area would have added hours to the trip – both ways.

When we finally reached our destination, it was pretty stunning. Enormous natural arches towered over the terrain.

“That… is… something,” Barrett whispered as he appreciated the sight.

“Not just something,” I added, “something special. Look up there.”

I pointed to a spot about midway up the inside of the closer arch. It was hard to see without looking closely, but a darker, more porous mineral deposit was stuck to the arch like a limpet.

“I do believe we’ve found a baby builder-microbe colony.”

“You know… I do think you’re right. How’d it get up there?”

“Spores maybe? Carried on the wind or attached to one of the airborne filter feeders?”

“Fascinating…” Barrett observed. “Do you think we could get up on top of the arch? I’m curious how the volatile organics coming off the baby compare to the more mature examples we’ve studied.”

“One way to find out,” I said, sizing up the best way to scale the arch.

It was not an easy ascent. If it wasn’t for Enlil II’s 0.69 Gs, I don’t think I could have done it. For about the hundredth time I told myself I really needed to complete boost pack training – one of the few Constellation certifications I didn’t have at least some progress on.

“It’s a nest,” I said, as much to myself as to Barrett. “A nest made out of bones. And an amazing view.”

“Scan first, appreciate later,” Barrett reminded.

The upper part of the arch turned out to be smeared with a tacky slurry of adhesives and biomatter, with rivulets of it running over the edge and down the inside of the arch.

“It almost looks like the builders are getting ingested by the filter feeders and then excreted near the nest.”

“Spreading around the way birds spread seeds on Old Earth,” Barrett observed.

“Simple and effective, I suppose. And the individual microbes are small enough that filterers floating past the established colonies could just suck up huge numbers of them.”

“We have seen them spontaneously release big plumes of bioactive material,” Barrett observed. “So maybe it’s intentional? Like releasing spores?”

I nodded slowly, distracted by the broad vista of the forest stretching out in all directions. “Sounds plausible. Hey, there’s another cave about 750 meters to the southwest. Feel up for an extra stop?”

“I’m always up for another stop,” Barrett said. “As long as Moara gives the green light, let’s do it.”

We checked in with Intrepid and laid out what we’d found and our plan to travel to the distant cave. Moara agreed with extending the mission to cover the new location, but warned us to only push forward if the forest density allowed for the rover to make it. The cave was almost two kilometers from Intrepid, and if an expeditious return became necessary foot travel would be too slow.

The trip to the cave proved pretty straightforward. As we got closer the forest thinned out considerably – and just in time, since we had to open up the throttle to outpace a frisky cagebrain that seemed to have decided it wanted to snack on the rover. When we reached the cave though, we found yet another surprise waiting for us.

“I’m pretty sure that didn’t get here naturally,” Barrett said as I shined my light on the aluminum table and supply boxes stacked up just inside the cave. Progressing cautiously, we found a small camp a bit further in. That got us a bit concerned… what was someone doing this far out? Did they need help? Or, conversely, were they a threat to us?

We scoured every inch of that cave, found lots of little hints of human activity all over, but we never found whoever set up that camp. It seemed like the universe had decided to give us one last mystery to go with all the clues and answers we’d discovered over the course of this excursion.

Well, we didn’t exactly find ‘nothing.’ In the camp we found a suitcase with a number of stone artifacts inside. I didn’t recognize the source specifically, but I had a strong suspicion that I was looking at contraband antiquities.

“Like the old movie says,” Barrett pointed out, “this belongs in a museum.”

“Agreed. We’ll turn it over to MAST when we get back from the expedition. But for now, I think it’s time to get back to the ship. As much as I’d love to keep exploring, it’s time to pack up and head home.”

As we pulled up to the ship, I noticed with some amusement that a cagebrain was repeatedly trying to chew on the command module, each time flinching back as it came into contact with our shields.

“You guys OK in there?” I asked.

“Nothing to worry about,” Jazz answered, “we’ve just got a little animal friend trying to get to know us better. He’s harmless.”

“The real question,” Barrett posed, “is… do you want to go visit this new rock formation I just picked up?”

“Want?” I asked. “Sure. But dusks coming on fast and we already decided not to stay for another day. So as much as I want to, we’re going to leave that one behind. Let’s park the rover and start rigging for liftoff.”

I checked in with each member of the crew. If some of them had been disappointed after the Vytinium deposit didn’t pan out, now everyone seemed upbeat and satisfied with the mission. And why not? We’d taken in a beautiful planet, discovered dozens of new life forms, learned important clues about builder-microbes’ chemistry and life cycles, and even recovered a little bit of human history that might otherwise have disappeared forever into a dingy cave in the far reaches of space. The expedition to Enlil II was a big success, and proof that when the whole Constellation team gets together it can accomplish great things.

The last person I talked to was Jasmine Durand. She was on watch in the command module, and the two of us were alone.

“So how do you like working for Constellation?”

Jazz didn’t respond right away. Then, she said, “It’s not what I expected. It still feels… strange. I’m not completely here by my own free will, you know? And I wonder if Naeva is out there somewhere. If she knows I’m alive? If she misses me?”

“Do you want to go back to the Crimson Fleet?”

“I… don’t know. And I don’t think I’ll know for quite a while. And that’s not even… listen, can I be straight with you?”

I nodded. “Sure.”

“What you said to me the day we jumped to Petria… it really bothered me. I still don’t know if you were screwing with me, or if you’re just crazy, but I feel like… I feel like the others deserve to know about you and your… beliefs. And they deserve a chance to decide if they want to work with you.”

“That’s fair,” I said. “But I can’t tell them yet. If they find out before they make certain discoveries, before they find certain clues, then they’ll never make those discoveries on their own. It’s not fair to them for me to just hand them the future on a platter. But I’ll make you a deal. You help me get the Dauntless built, like you helped get Intrepid through her teething problems back on the Key, and I’ll make sure Dauntless does her shakedown cruise in the Procyon system. Sam, Sarah, or Andreja will find something there. I’m not sure which one, but one of them will. And that’ll set things in motions where they’ll learn the truth about me.”

“That’s a big ask,” she said, a little icily. “It wouldn’t be the first time you lied to me.”

I looked left to the companionway, making sure no one was entering the command module, before I said. “Would it help if I showed you something unquestionably supernatural? Something to prove I’m not just a crazy person making up wild stories?”

Jazz seemed confused. “What do you mean?”

I centered myself with a deep breath and concentrated on the technique I’d learned in Temple Sigma. Reaching out my consciousness, I kneaded and stretched the veil between parallel universes until, with a flash, there were two of me there. My other self was crouched in a martial stance, dressed in a Crimson Fleet captain’s uniform and clearly spoiling for a fight. When she saw Jasmine, however, she relaxed and uncoiled.

“Jazz?” Other me asked. “You’re alive? How?!”

“What. The. Fuck?” Jasmine Durand whispered in a voice standing somewhere between amazement and terror.

“This is the truth of the universe, Jasmine,” I said. “We all live infinite lives in infinite universes. In an infinite number of different universes, I discover the secret of rebirth. In an infinite number of universes, I don’t. And every possible permutation of those two outcomes happens as well.”

Other me sighed, then stood up straighter. “I won’t be here for long,” she explained. “Jazz, don’t trust Mathis. He’s going to sell you out to UC SYSDEF in order to get to Naeva.”

Then she looked to me. “Thanks for the chance to see my best friend again, sister. But I can already feel the pull. Be safe.”

And with a flash and a twinkle of stardust, the parallel version of me was gone.

“Do you understand now why I can’t just come out and tell everyone about what I’ve discovered? Will you trust me that I know – from experience – when it’s the right time to tell them?”

Jasmine just shook her head. “I don’t know. I don’t know… anything, do I? You just took every rule and certainty I’ve ever had and tossed them out the airlock, so I need some time to process this. For now, just give me some time.”

End log

July 6th, 2330

Days Elapsed: 14

Fuel Consumption: 0

Fuel Acquired: 0

Fuel Remaining: 171.92 kg

Injuries Acquired: 0

Lifetime Injuries: 4

Today I Learned…

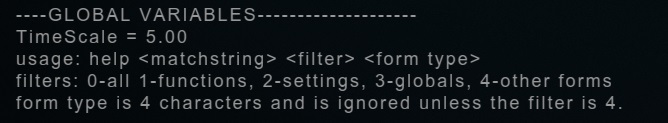

For some time I’ve been noticing that the amount of time that passes on space travel seemed wrong. On closer examination, I discovered why. Normally, time in Starfield runs at 15:1 (4 minutes of play time equals 1 hour in the game world), but when you board your ship it changes to 5:1. As a result, even though they ‘felt’ the right length, a lot less time than I expected passed during interplanetary travel.